Redesigning A Sicko Board Game Map

Web And Starship is a 1984 game by Greg Costikyan and West End Games. It is a space opera wargame, with the enticing subtitle "Earth Between Two Foes", and in many ways is a classic counter wargame.

It was introduced to me with two inducements: firstly that it was a real-deal asymmetrical wargame, mostly in respect to methods of space travel. One alien race, the Pereen, send probes to distant stars to build their Web, through which they can travel between instantaneously. The probes are limited by sublight travel speeds, and if a web nexus is destroyed it can instantly leave troops stranded. The other alien race, the Gwynhyfarr, travels by faster-than-light travel, using transports. They can go anywhere but their jump range is limited and slower. Earth and humanity starts in between these two alien races, and with a smidgen of both of these technologies, which can be upgraded over the course of the game.

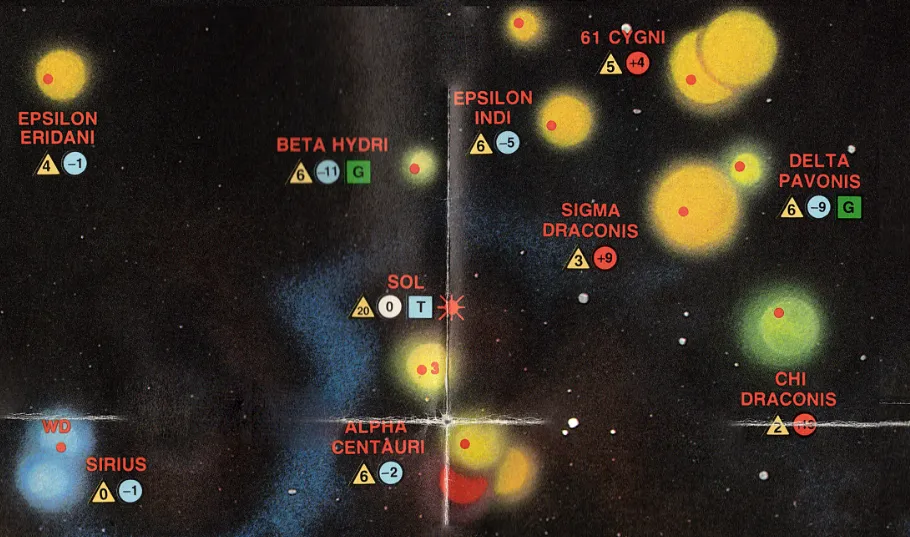

The second inducement was the map – a real-stars-at-real-distances map with only light abstractions. Each star has a lateral position on the map, and a ± value above the ecliptic, centered on Sol. Thus the true distance between two stars is first measured with the provided ruler, then the z-axis delta provides a lookup value on the provided table. Or you can employ the Pythagorean theorem, but that's your business.

Wild! Fun stuff, extremely my shit. But [turning the chair around] you know what's also extremely my shit? That's right, a game that's actually fun to play and engage with as an object, willing to sacrifice a few details to produce a fun experience. Also, if I would barely be able to put up with this shit, my friends surely wouldn't. I am the local maxima for space-sicko board games, and I know it.

I did still want to play the game though, because it looks fun! So I set out on a project to redesign (or rehabilitate) the map into something more playable. I've talked before about how simulation can affect pacing and W&S definitely falls into the trap. Simply exploring the options of moving from one star to the next requires a multi-step process of trading a ruler around and consulting a lookup table. I want to preserve the real distances but skip over the manual calculation part and over to the developing a strategy and playing the game.

Forgive the scanning artifacts

Forgive the scanning artifacts

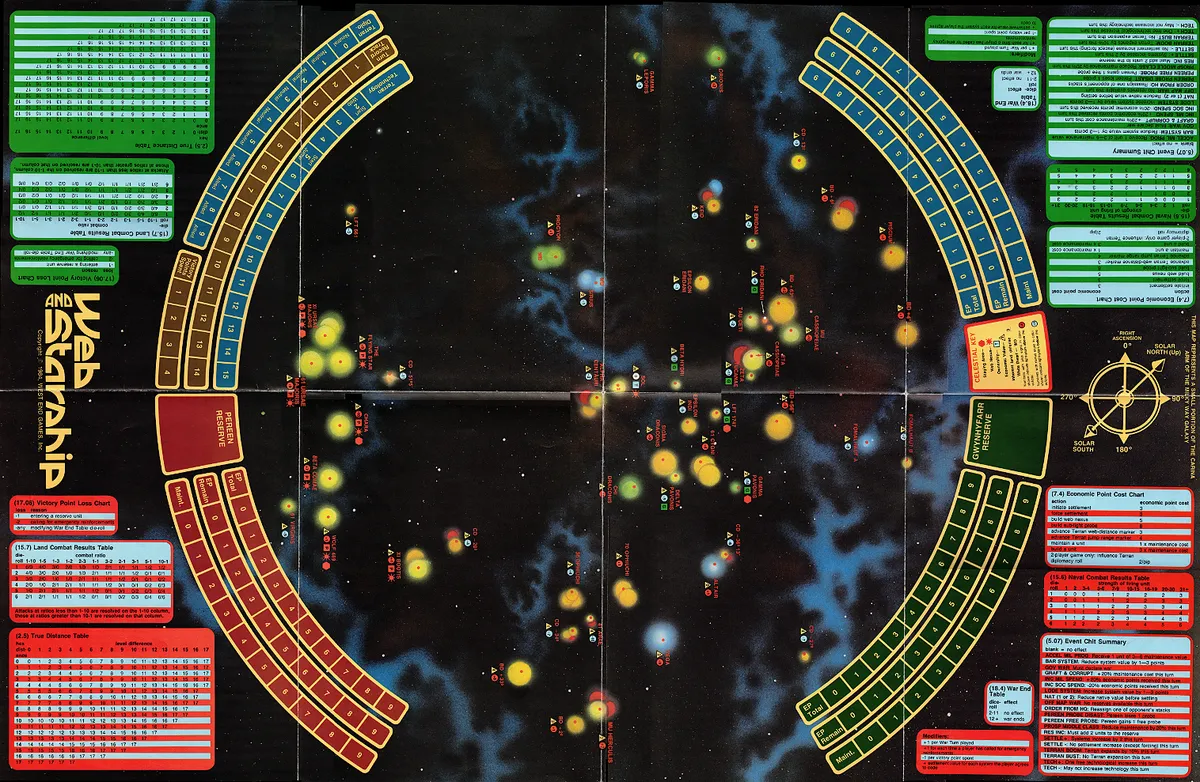

The whole map! Fifty two stars. Just shy of 800 valid links between stars. So I thought it would be an interesting side project and graphic design experiment to see if I could get all that information embedded on the map. And, well, I mostly failed. But I learned a lot and I think had a solid outcome at the end.

A Lot of Lines

It's generally useful to get bad ideas out of your head quickly. The good ideas need space to begin to crystallize, until you gently reach into your mind and take the idea-crystal out into the real world to throw it against the brick wall of reality, to see if it shatters.

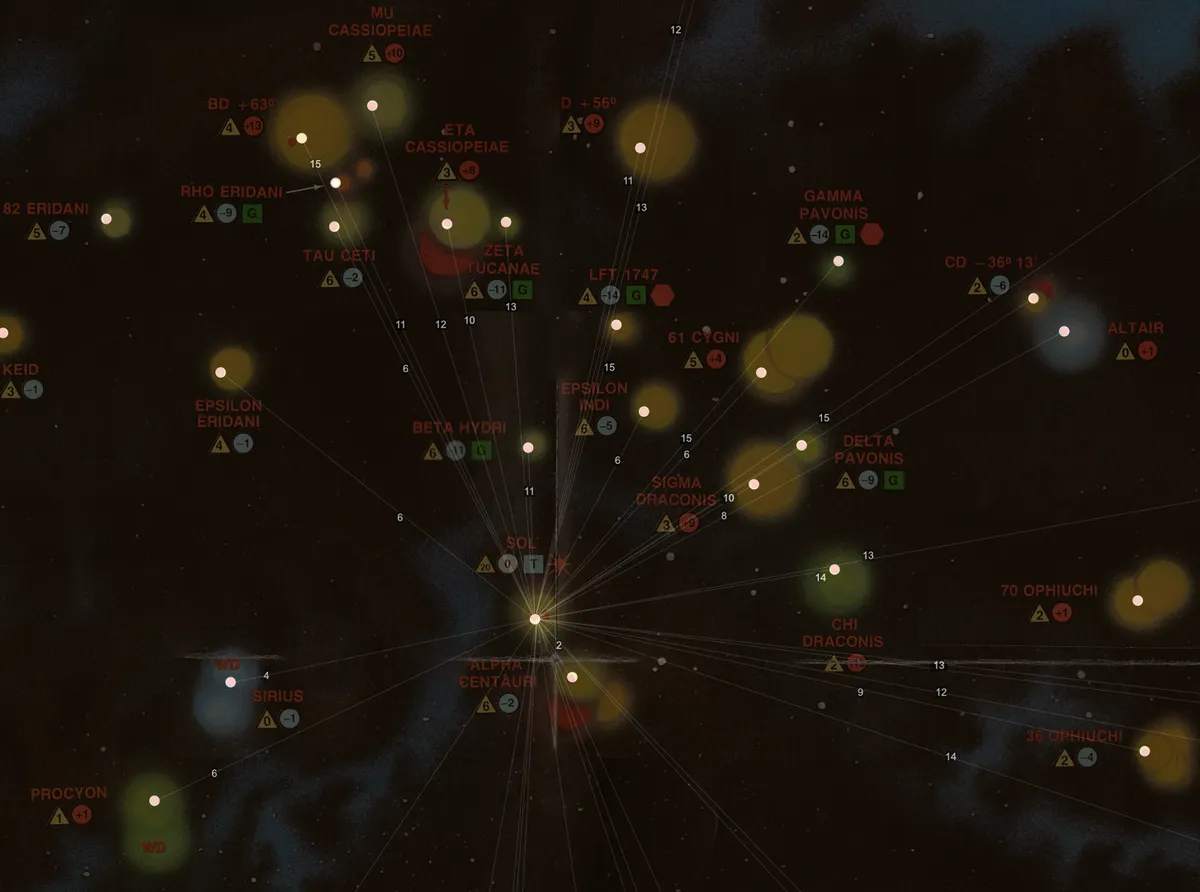

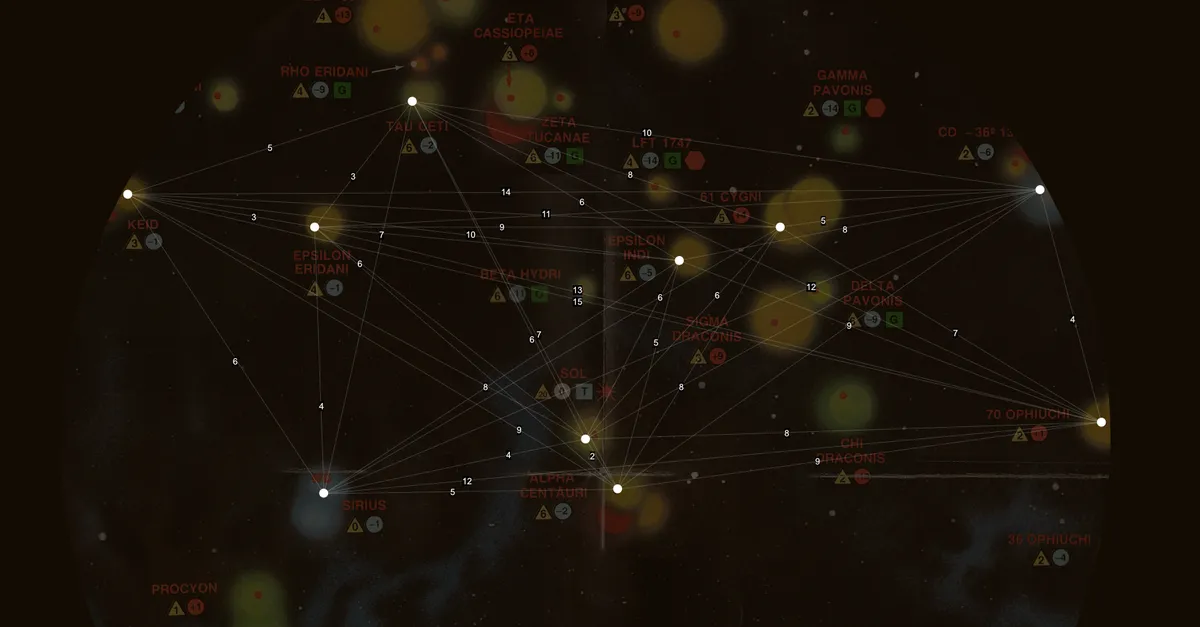

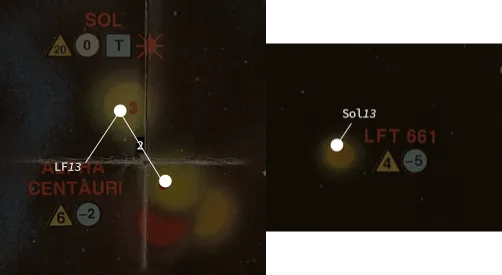

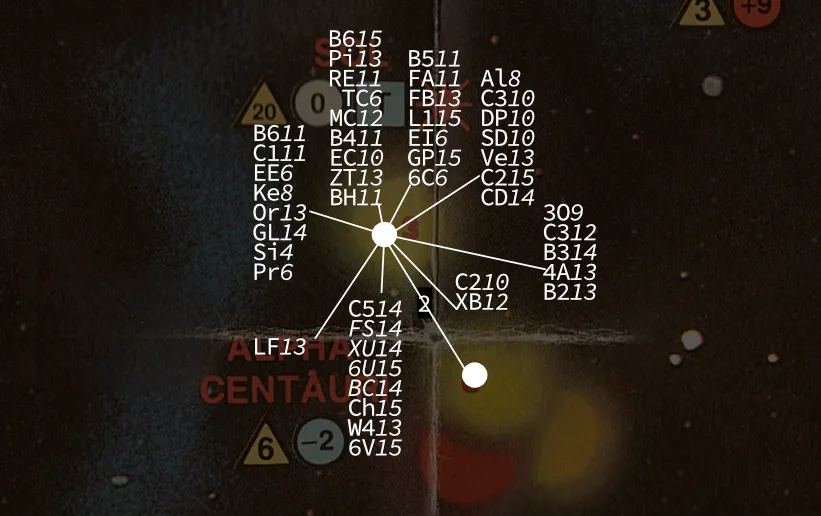

Anyway, the first bad idea: draw a lot of lines in between stars, printing the Movement Value (MV, or 2ly) between them. This works great... for one star. The image above is not even every link Sol has with another star and it's already becoming crowded. While this is unquestionably the most direct way to deliver information to the player, it does not scale well.

Fair enough then, perhaps lowering the density of stars might do the trick?

The map with an 'inner sphere' and 'outer sphere'.

The map with an 'inner sphere' and 'outer sphere'.

Close up of the inner sphere.

Close up of the inner sphere.

Well...maybe! You can see this attempt had a lot of work put it into it, as I did think this would begin to pan out. Certainly the 'inner sphere' map is generally readable, especially if some links share number callouts for their distances. A few cases where lines are close enough that something needs to be nudged to help disambiguate labels, but not too bad. Let's look at the outer sphere:

Not good, huh? Very crowded (and this isn't even complete) and lots of difficulty telling which labels go to which lines. Worse, some lines are so crowded it required modifiers: a line might cross a [6] but if it later crossed a [+2], the value for that line was 8. We're starting to lose the benefit of this system, in that you can get the immediacy of a line with just a straight number. Not to say what things might look like for links that had to go between the spheres. It was around this point I wish I still had the CAD skills I once did for a previous job, or some experience with data visualization tools to begin quickly reconfiguring the orientation or presentation of this space.

Lots of Labels

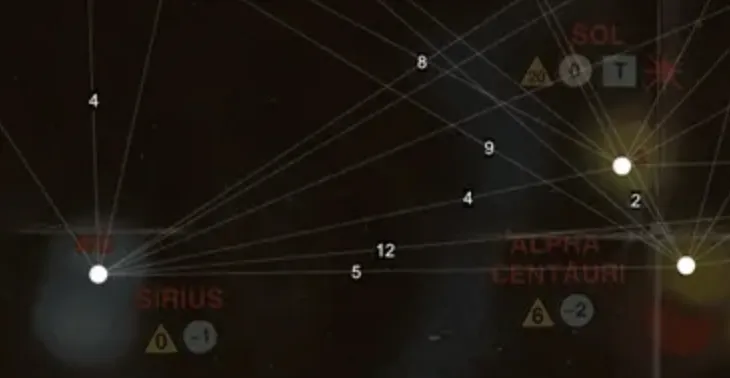

Let's try something new. Each star gets a line pointing to the other star, an abbreviation of the name, and the distance to that star. No searching around the map for the right label on the right line, no adding numbers together. There are duplicate labels (as in stars A and B both have to show numbers for the other) but that's.. ok? Maybe? Here is Sol with every label:

Bad! At some point I had to start grouping labels and the line would have to be more a suggestion than true line. Even so it's very crowded, and you have to do some searching on the map to find the corresponding star. I think this idea would hold water if the map simply had fewer stars. When playing the game, you need to know what other stars you can access from a given star, and you can do that here.

Hexes

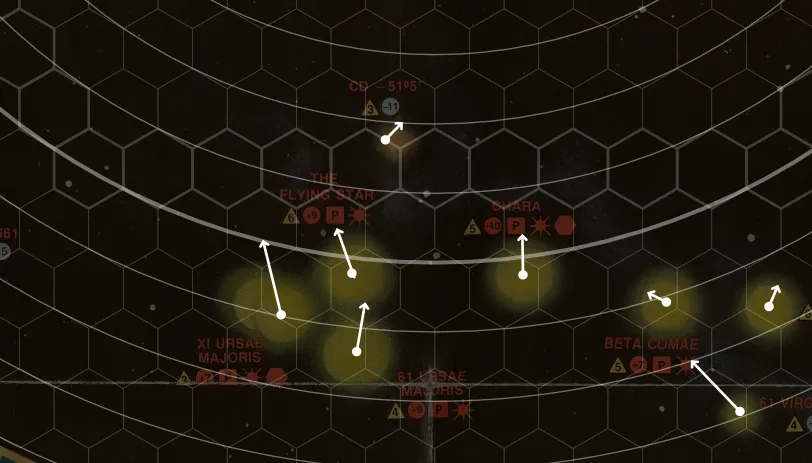

Say, friend, what's the most accurate two-dimensional tessellation, used by wargames for decades? The humble hexagon, of course. What if I could rely on player's innate ability and desire to count little tiny spaces on the map? This would require still consulting the height lookup table, but at least you can count hexes a lot faster than passing around a ruler. It even kind of looks nice, doesn't it:

But of course, hexagon tessellation is not distortion free. This second image has three elements to be aware of: the thick/thin hexes, the thick/thin lines, and the arrowed lines. The thick hexagons and thick lines correspond to ten MV from the center of the map. Observe how distant they are. So, each star has correct it's hex position so it will be the right distance from the center of the map.

This of course begins to create inconsistencies between the stars. Since the distortion correction is only relative to the center of the map, some stars would need an 'override' value that tells the player to ignore the hex distance and use the printed value instead. Learning this I was surprised how often the hex map was actually right, because the number of overrides just kept growing. Aside from an information point of view, should the override print the true distance or just the lateral distance? So dies the hex idea.

What if the line is the information?

I'm pretty annoyed at this point. I'm learning a lot, but this project is going nowhere fast and I'm getting kind of sick of looking at these maps and these star names. Fuck you, Gamma Pavonis and 36 Ophiuchi. George Lucas was right not to use that name for the Jedi. You know what's a cool star name? Sirius. Epsilon Eridani. Wolf 489. Those are poetic names. When I see Xi Bootis I say "kai-booty" in my head and smile to myself.

I think about the game itself. One player only cares if stars are within 12 MV of one another. Another player only cares about stars that are 8, 10, and 12 MV. The Terran player is the only one whose MV capabilities change over the course of the game. Maybe I could let the Terran player do all the measuring and ruling, and encode all the information on the map for the other two players?

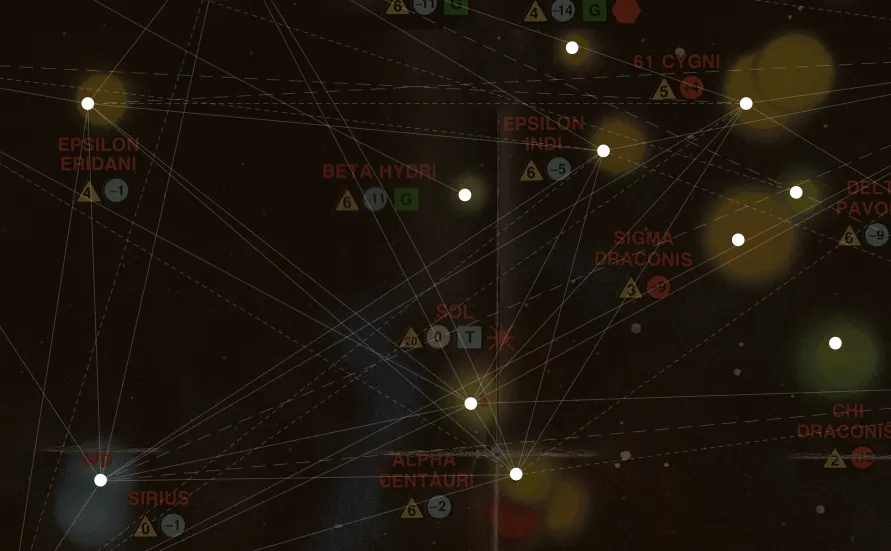

Interesting! Honestly, could be worse? Crowded of course, but not any more so than before. The solid lines here are links <8, and the dashed lines are 9-10 and 11-12. It gives a good sense of what two of the players can do at a glance, which is helpful.

But thinking about this more, I came to two realizations. This is a wargame, and a player in a wargame needs to understand what they can do and what their enemy can do. The two players relying on these lines will still need to know the other star distances to be able to play against the Terran player. The other realization is that the lines on the map begin to crowd out the actual possibility space of the map. Just because a line is not present doesn't mean two stars are not linked by the Terran player at some point in the game, since their movement capability can exceed the others. So this map actively works against the players as they try to hold in their heads which stars are possible to move in between, beyond what the lines say.

The End is the Beginning: Spreadsheets

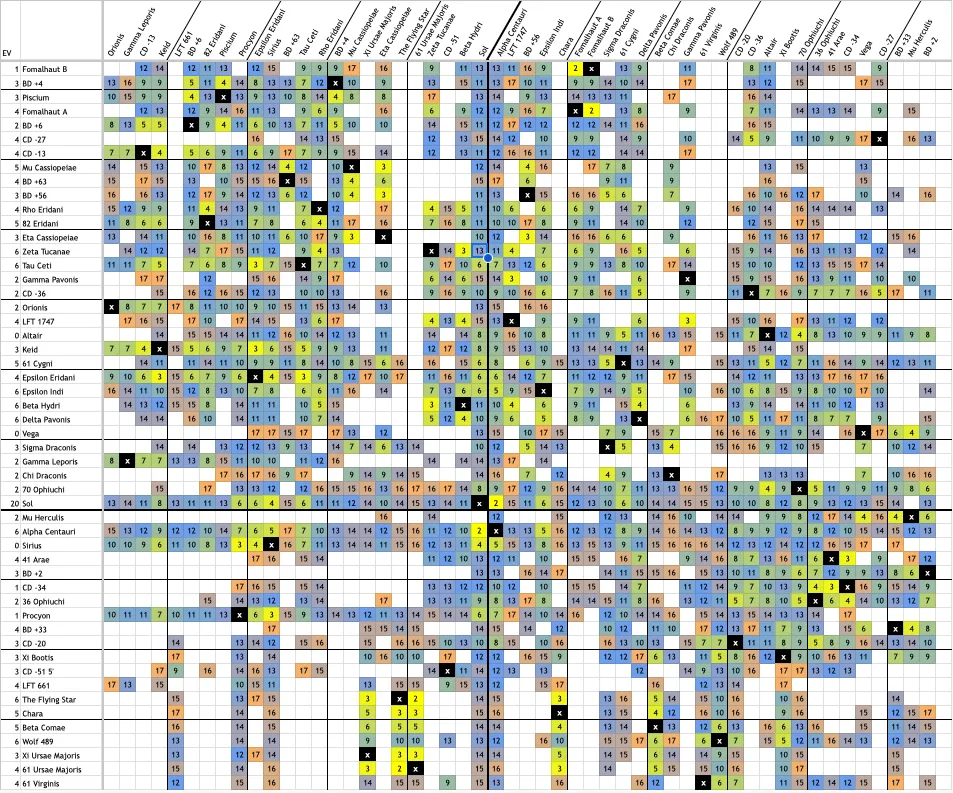

All this time I've been working off a spreadsheet of all MV values, compiled by BGG users 'stephenhope' and 'M St'. It's pretty basic, just a matrix of the stars. There isn't much order to it, and it looks nice enough for a spreadsheet.

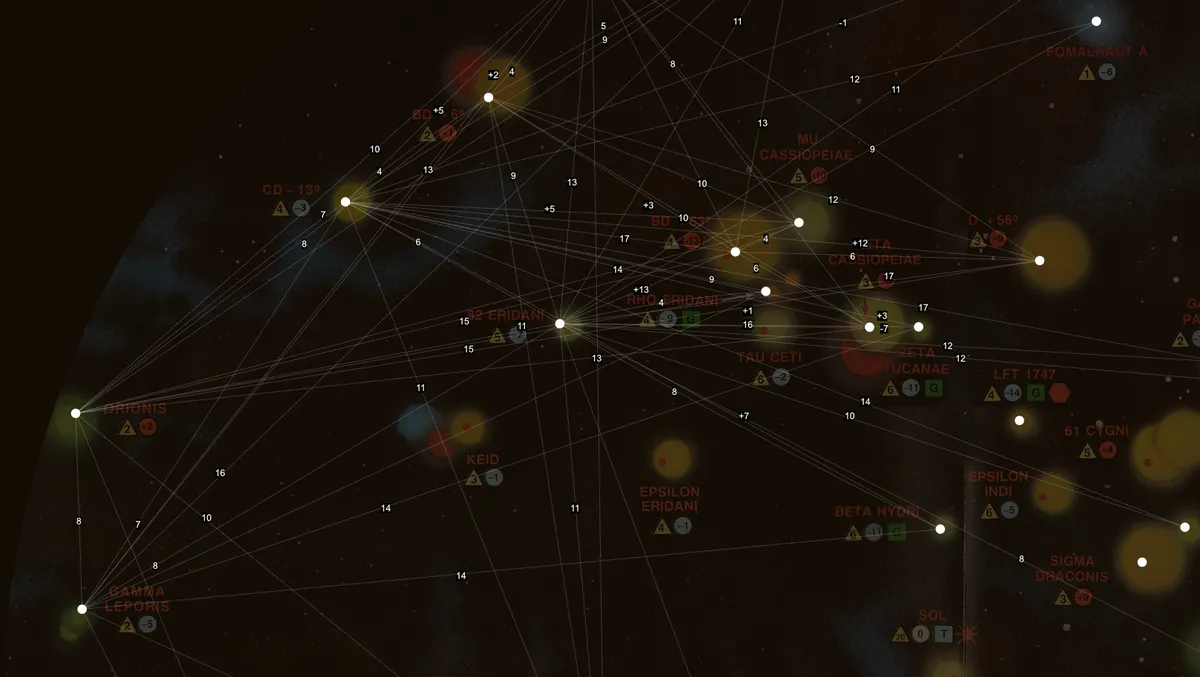

I had a thought, in between turning this problem around in my head, to at least reorganize the spreadsheet into something easier to use. Say, putting each star in order from left to right and top to bottom. Maybe some color filters for the MV values, to help your eye easily sort through the data. And hey, as a nice touch, where the star row meets its column, a little white x on black.

Well! That looks nice, and pretty fucking helpful? Each star is kinda in the right spot, not exactly of course but certainly close enough. Colors also lead your eye to the clusters, and you can see which stars are close to one another, and which are visually close but actually far apart. Your eye can track along rows and columns very easily, and naturally there's no confusion as to what number goes to which pair of stars. It's essentially the whole map normalized.

I like this a lot. At this point I messaged my sicko friends and said "we're good to go on this game." I haven't played yet, and I will report back with how this method worked, or as the idea has hit the brick wall of reality.

Conclusion

So, what's to learn from all this? Well, spreadsheets stay winning, definitely. Projecting this many points from a sphere onto a plane is hard. If I was making this game from the start I would abstract the star locations further, make the MV values coarser. Instead of 2ly, a MV is equal to 4 or 5ly, and lowering the maximum. Or grouping stars into clusters, and stars within that cluster have a finer grained distances but the distance between each cluster is just one big number that's easily remembered. Ideally you want to print the value on the map, even consulting a spreadsheet is not ideal for most people. But, so it goes.